Android apps are much easier to modify than those of traditional desktop operating systems like Windows or Linux, and there’s primarily only one way to modify Android apps after they have been compiled from source: dexlib. Even if you’re actually using Apktool or Smali, they are both using dexlib under the hood. Actually, Apktool uses Smali, and Smali and dexlib are part of the same project.

Why is this important? Any app which has had malware injected into it or has been cracked or pirated will have probably been disassembled and recompiled by dexlib. Also, there are very few reasons why a developer with access to the source code would use dexlib. Therefore, you know an app has been modified by dexlib, it’s probably interesting to you if you’re worried about malware or app piracy. This is where APKiD comes in. In addition to detecting packers, obfuscators, and other weird stuff, it can also identify if an app was compiled by the standard Android compilers or dexlib.

APKiD

APKiD can look at an Android APK or DEX file and detect the fingerprints of several different compilers:

- dx - standard Android SDK compiler

- dexmerge - used for incremental builds by some IDEs (after using dx)

- dexlib 1.x

- dexlib 2.x beta

- dexlib 2.x

If any of the dexlib families have been used to create a DEX file, you can be fairly suspicious it has been cracked and it may have been injected with malware. For more info on how we used compiler fingerprinting to detect malware and cracks, check out our talk Android Compiler Fingerprinting.

Detecting dx and dexmerge

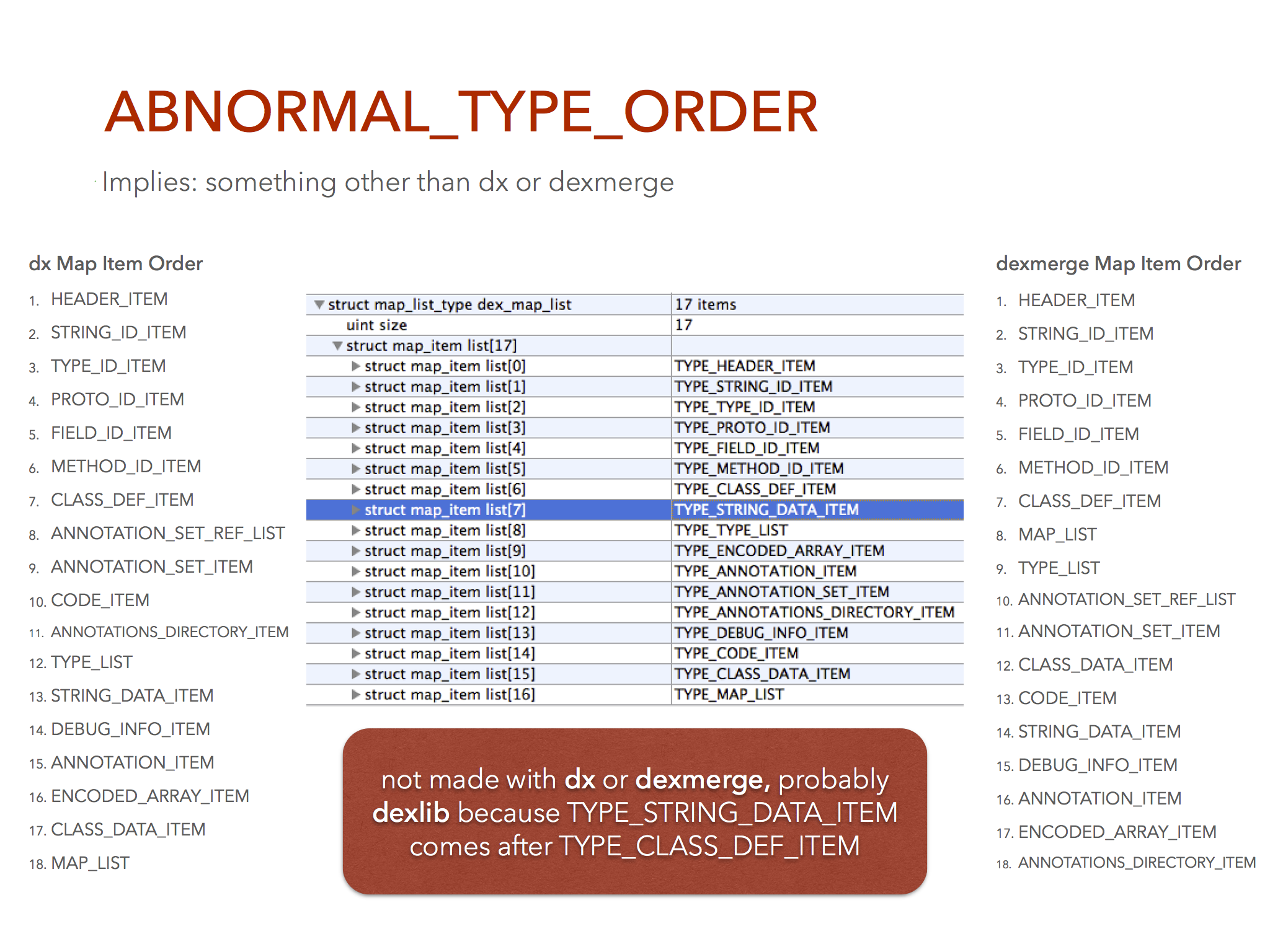

The main way dx and dexmerge are identified are by looking at the ordering of the map types in the DEX file.

This is a good place to identify different compilers because the order is not defined in the spec so it’s up to the compiler how it wants to order these things.

In order to have something that’s copy / paste-able, here’s some Java code for the normal type order:

|

|

The dexmerge type order was derived by looking at DexMerger.java. I got the typeIds order by looking here.

|

|

In general, the format of a DEX file and the items inside are like this:

|

|

This list may be handy for ongoing research into fingerprinting different compilers.

Detecting dexlib 1.x

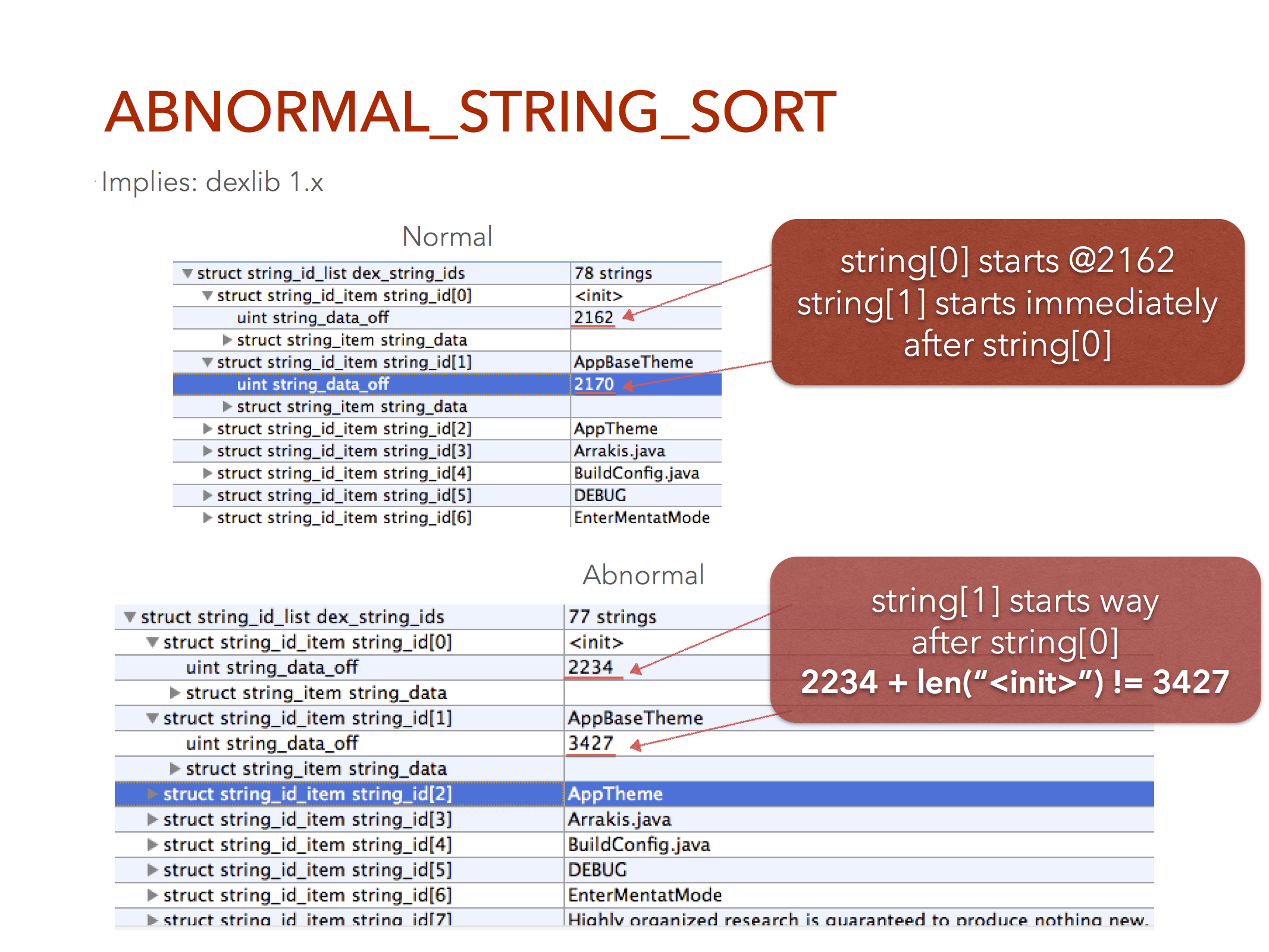

This is the first library that allowed disassembling and compiling of DEX files without the source code. It was created by Ben “Jesus Freke” Gruver. It’s detected primarily by looking at the physical sorting of the strings.

The DEX format requires that the string table, which list all the strings and their offset into the file, must be sorted alphabetically, but the actual physical ordering of the strings in the file are not necessarily sorted. So while dx sorts strings alphabetically, even though it doesn’t have to, dexlib seems to sort them physically based on when they’re encountered during compilation.

A lot of commercial packers and obfuscators and certain malware families still use dexlib 1.x under the hood because it’s pretty solid and they’re too lazy to update.

Detecting dexlib 2.x beta

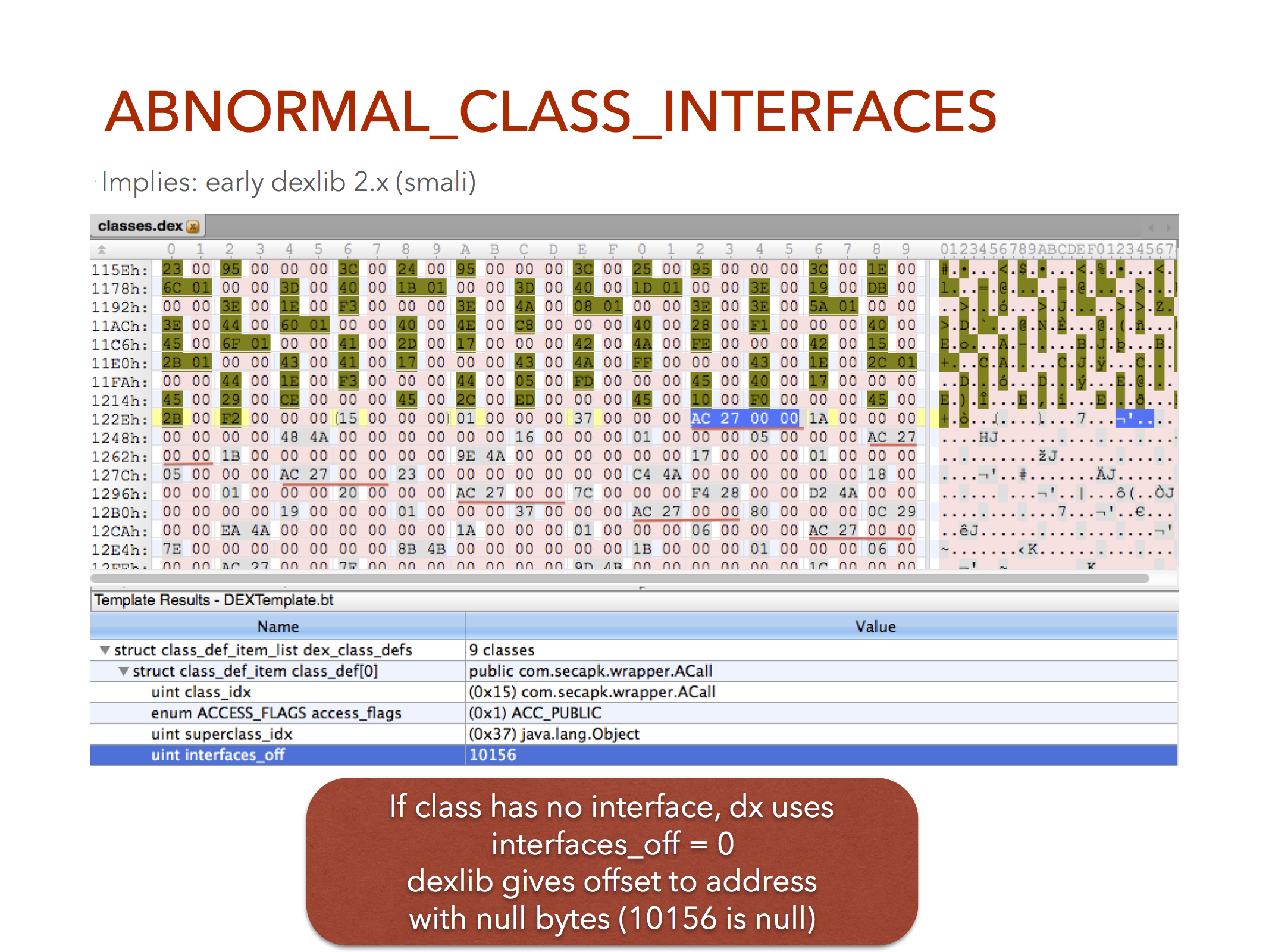

Dexlib 1.x was rewritten into dexlib 2, and while it was in a beta release, we noticed that it did something weird with how it marked class interfaces.

You can see AC 27 00 00 all over the file. That’s the offset to the “null” interface for classes which don’t implement any interface. It’s a good example of how flexible the DEX format is, because I would figure this wouldn’t run at all, but it does. The dx compiler just uses 00s to indicate that there’s no interface.

This was removed before dexlib 2.x was moved out of beta.

Detecting dexlib 2.x

This compiler is also detected by also looking at the map type order. Assembling a DEX file is complex and there are a lot of tiny little details you need to mimic to create an absolutely perfect facsimile. That’s a lot of extra work most developers don’t want to do.

As an aside, I spend a lot of time using this library and looking at it’s code while working on a generic Android deobfuscator called Simplify. And I’ve got to say, it’s some really impressive and clean code that I’ve learned a lot from. Kudos to Ben.

Using APKiD

The usage of APKiD is quite simple. You just point it at folders, files, whatever, and it’ll try and find APKs and DEX files. It’ll also decompose APKs and try and find compressed APKs, DEX, and ELF files. Here’s output of an example run:

|

|

You can see that the test samples of DexGuard and DexProtector both use dexlib 1.x. APKiD also supports JSON output so it’s easier to integrate into other toolchains:

|

|

Ideas for the Future

This post leaves out all of the Android XML fingerprinting details Tim researched that can identify tools like Apktool. We still need to add these fingerprints into APKiD.

There is also a library called ASMDEX which looks capable of creating DEX files. At the time of this original research a few years ago, I didn’t have time to look into it, and no one was talking about how to use it. A lot of the stuff was over my head, but I’ve since had a lot of practice using ASM to create Java class files, so I think I can manage now. It would be nice to add fingerprints for ASMDEX. Anything created by that would probably be pretty weird.